A devastating disease killed millions of fish and disrupted their migrations across the Columbia River in the 1980s. Microbiologist Jo-Ann Leong never imagined that her quest for a new vaccine would ultimately change the world we live in today. From researching tissues to studying coral diseases, her path to winning the Lifetime Achievement in Science Award turned out to be a tsunami full of surprises.

This award honors exceptional and significant contributions to science over the course of a lifetime either through research, scholarship or teaching.

Finding a fascination with viruses

Obtaining her Ph.D. in Microbiology and Virology at the University of California, San Francisco was just a drop in the bucket for the serendipitous tsunami.

Many miles away in Corvallis, Oregon, a faculty member suddenly left the College of Science, leaving a position in virology open.

While her peers raced to send applications to top medical schools across the country, Leong considered leaving the bustling city for a change of pace. It was a gamble, considering “going to Corvallis is not what my classmates would normally pick,” she said.

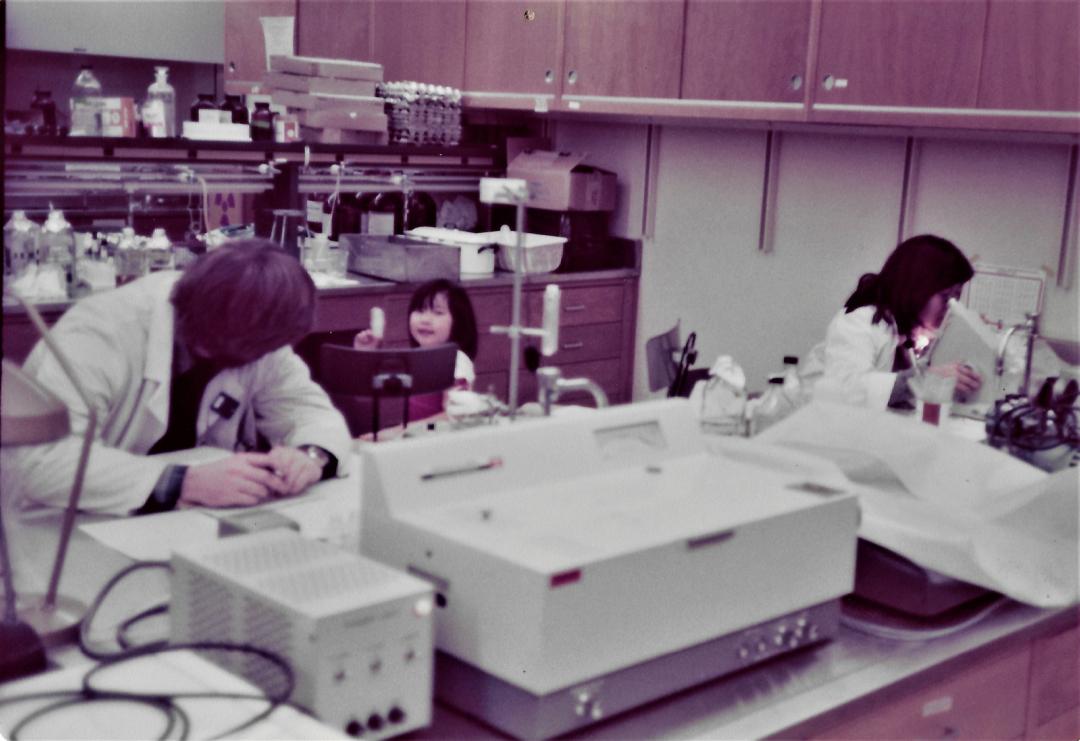

After a phone call and interview, she landed the position as an assistant professor. When she arrived in 1975, she started as a fish out of water, attempting to start a virology lab for the first time. For a while, she was the only woman professor in Nash Hall.

Leong balanced work with raising her two-year-old daughter by herself. Her husband, constrained by the demands of his anesthesiology residency in California, couldn’t relocate with her. “We moved the family to Corvallis and he would fly up every other weekend to be with her.”

Learning how to run a virology lab, mentor graduate students and teach courses proved to be more difficult than she thought. At the same time, it was the perfect setup for groundbreaking hands-on learning opportunities.